Ne hoc nescias, Lector, omnia pene, quae Morus disputat, & et loquitur, ex Ciceroniano Erasmi dialogo assumpta sunt.

You shall not forget, dear reader, that nearly everything Morus says and states is taken from Erasmus' Ciceronian dialogue.

(Dolet, Dialogus 8,2–7)

Introduction II: Étienne Dolet's Dialogus

Content

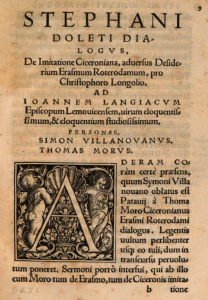

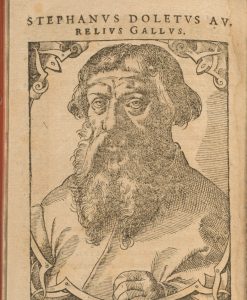

In 1535, the French humanist Étienne Dolet (1508–1546), better known as printer, aggressor, and heretic (Chassaigne 1930, Lecompte 2009, Coninck 2019), published a book with the long title:

Stephani Doleti Dialogus, De imitatione Ciceroniana, adversus Desiderium Erasmum Roterodamum, pro Christophoro Longolio

The text is a dialogue between Simon Villanovanus, teacher of Étienne Dolet and ardent Ciceronianist of his time (see Henderson 1987, Bingen 2013), and Thomas Morus, English humanist and best friend of Erasmus of Rotterdam, the famous "Fürst der Humanisten" (Schultz 1998). The 200 pages long text is thus, at first glance, a discussion of the concept of Ciceronian imitation (De imitatione Ciceroniana) – a subject that has been discussed very often among humanists at that time – held by humanists of the second row (compared to Erasmus' popularity!). But already with a closer look at the title, it appears as the fervent defence of a pure, Cicero-oriented form of humanist philology, represented by Dolet himself, his teacher Villanovanus, and his teacher Christophe de Longueil (see Simar 1911), against Erasmus of Rotterdam (adversus) – who defined in his text Ciceronianus sive De optimo genere dicendi (1528) that the best Ciceronian was the one who was less similar to Cicero who would have favoured, given that he was still alive in 1530, Christian and not antique, 'pagan' knowledge and words:

Porro quum vndiquaque tota rerum humanarum scena inuersa sit, quis hodie potest apte dicere, nisi multum Ciceroni dissimlis?

(Erasmus, Ciceronianus 636,33–35)

This does not mean that Erasmus wanted to abandon Latin being the humanist language par excellence but that he wanted to accept Christian Latin words that were not known in Classical antiquity. Meanwhile, Dolet’s idea was to keep Latin language as it is transferred by antique authors, and to open the own mind to be able to understand antique Latin in new contexts.

Henceforth, Dolet’s Dialogus touches the roots of humanist philology, asking himself on the status of Latin words in the Early modern period, and confronting two groups of humanists. This could be visualized as follows:

Mode of communication

The outstanding attribute of the Dialogus is thus its mode of communication. Villanovanus and Morus are not only talking to each other: Morus is reading the Ciceronianus of Erasmus to his dialogue partner who is then answering freely. One could say that Morus is only quoting – as quotation was not yet present in an academic sense and as plagiarism was just coming up with the printing press, quotation was a lot easier to handle at that time without having law consequences: Quotation does not mean, as in today’s academic contexts, to write down precisely what is written in another text and announcing where the quoted text is to be found. On the contrary, it could be used as a strategic way of competing with other texts written by other humanists (imitatio and aemulatio, again).

On the following page, there will be analysed the different ways of quoting Dolet used.